For the independent traveler, there exists mythical place, lodged safely in ones mind’s eye-a place that is off the beaten track and fairly unspoiled by tourists, authentic and picturesque, and with just enough creature comforts to make it feel both relaxing and like home. These places are often difficult to find and often disappointing. But thanks to a tip from an FCCSD friend, Susan Keogh, our family, on a recent trip back to China in March, found just that special place, a place called Zhaji.

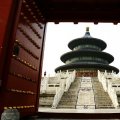

Located deep in the southwestern corner on Anhui province, Zhaji is a small Ming Dynasty era village, surround by rice paddy, mulberry bushes and tea. It is an overwhelming agricultural environment, where water buffalo are more common than cars . There are no major bus terminals or train stations nearby. One must arrange transportation to and from Zhaji’s nearest big city neighbors-Nanjing which is three hours north, Huangshan which is two hours south. Zhaji is nestled in a small valley, with a pagoda-clad hill overlooking the village. Save for small groups of artists that come to sketch the picturesque alley ways and the meandering stream that runs through it, Zhaji is devoid of tourists. It is a place where there is a lot to see and explore but not much to do, a place, that for our family, felt like home within a matter of hours.

Much of the credit for goes to owner and proprietor of Zhaji’s lone tourist accommodation, Frenchman Julien Minet. In a story that probably would be the makings of a short novel, he purchased the village’s most decrepit courtyard home several years ago and lovingly restored it. He now provides the two upstairs rooms for visitors. The architecture in southern Anhui province is unique for its high white walls, black tiled roofs and stone and woodwork. A step into Chashiwu, the name of the ‘inn’, is like having one foot in the 16th century and the other in an edition of Architectural Digest. From the high white walls, stone floors, wood beams and the handmade wooden furniture-all purchased and produced in Zhaji, and splashes of red and blue on the cushions in front of the fireplace, it is a place of utter simplicity and comfort. The bedrooms upstairs sported solid wooden bedframes with huge white comforters, a bathroom with a HUGE wooden bathtub, and a small private deck looking over the neighboring homes and further out into the fields. Back downstairs, the windows and huge wooden doors open out onto the courtyard, where in mid-march the peonies and fruit trees were just beginning to bloom. Beyond the courtyard walls one could see the tiled roofs of the village, and the mist-covered mountains beyond

After lunch we headed out into the village for a guided tour, led by Julien. Our daughters, Mae,age four and Zoe, age seven, followed closely behind him as he took us to his favorite stops-a calligrapher’s brush-making shop, an old clan house that had been turned into the village museum, the woodworker who made small bamboo stools and had a private museum of porcelain and artifacts upstairs in his home. Twisting and turning through alleyways, we came across Julien’s friends, whom he would stop and speak to in fluent Mandarin. And then the high white walls became less frequent; crossing over the small river we then headed out into the countryside, tramping along muddy paths cutting through paddy , where men with their water buffalo were ploughing for the upcoming planting. We walked through the local cemetery, passed small plots of vegetables and groves of fruit trees, skirting outlying homes and grazing livestock. There was much to see in this working village, and from the brood of newborn chicks to the stacks of harvested bamboo, the baby water buffalo or the small bridges cutting back and forth across the river, our girls were engrossed and highly entertained. Julien, a natural teacher, provided extra entertainment, by explaining in simple terms the architecture and the history behind the things that caught their eye, including ‘Magic Bridge’ where packs of cookies were said to magically appear for those that were good (they DID!) and M & M Tower, the pagoda overlooking the village and the source of all such candied delights. Julien explained to the girls that legend had it that hidden doors would open from the pagoda and all the M&Ms in the world could be found here. The girls spent twenty minutes pushing on this stone structure, looking for these hidden doors, with Julien even boosting them onto his shoulders for a closer (and higher) look. Walking down Zhaji’s only paved road, we wandered into small stores, buying drinks and snacks, and arousing a tremendous amount of curiosity about our family. More than any other place we travelled, our preprinted cards of explanation came in handy and brought yet more people into the street for a quick look at our unusual family.

Sitting by the fire in the evenings, Julien explained his interest and desire to preserve this part of China, one that is not so much being outright destroyed but rather one slowly eroding due to the loss of viable families and sustainable employment. With most young people leaving the village in search of work, Zhaji, like many rural places in China, is becoming home to only the young and the old. So Julien helped set up a “Zhaji Artisans Club”, to help a small handful of local entrepreneurs stay in the village while simultaneously making a living in a skilled profession, and selling their goods on the internet. Village preservation, in his mind, is about preserving a way of life and the ability of people to sustain themselves in their ancestral villages and not flock to the city leaving parents and children behind. The stories he shared were quite sad, evidence of the strain many families from poor villages are experiencing in rapidly-changing China.

He and the ‘auntie’ who manage Chashiwu were thrilled and extremely curious about Zoe and Mae, particularly Zoe, an Anhui native. As Julien explained, “These are Chinese girls who have lost a deep element of their heritage, like many Chinese today. I want to make them feel engaged about everything they are seeing, “he continued, “and to give them that special connection to China. I preserve this kind of China out of an intellectual curiosity, so to have adoptees here gives the meaning of my work an entirely different perspective. I want them to leave here feeling the magic of their country.” In this endeavor he succeeded brilliantly.

On the last day we took one last walk through the village, and as Ian and I poked our heads into small homes and shops, a few selling rustic artifacts and antiques and painting supplies, Zoe and Mae charged ahead down the small, winding alleys. As I lost sight of Zoe but could hear her laughing voice echoing off the high, tiled walls, I realized that my Anhui girl had made Zhaji, for just a short time, her home.

No comments:

Post a Comment